Here's another guest post from Woody Bendle exploring Thomas Edison's focus on inventing products that sell and what that means for companies chasing cool ideas irrespective of whether they really solving consumer needs:

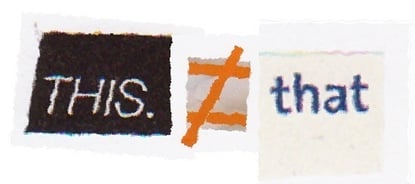

Chasing Cool Ideas vs. Solving Consumer Needs

In honor of Thomas Edison's 165th birthday (February 11, 2012), I've chosen to write about what I feel is perhaps one of his most significant and enduring contributions to the field of innovation. It isn't an invention or innovation, but rather it is an insight:

Create things people want, need, and are willing to buy.

While this seems so obvious, I'm continually amazed by how many new products and/or services fail - primarily due to the lack of understanding about the needs of market. Let's first look at Edison's own eureka moment.

The year is 1869. A 22 year old Thomas Edison receives his first patent for the invention of The Electrographic Vote-Recorder - US Patent 0,090,646, wherein Edison describes: "The object of my apparatus which records and registers in an instant, with great accuracy, the votes of legislative bodies, thus avoiding loss of valuable time consumed in counting and registering the votes and names, as done in regular manner; …"

The year is 1869. A 22 year old Thomas Edison receives his first patent for the invention of The Electrographic Vote-Recorder - US Patent 0,090,646, wherein Edison describes: "The object of my apparatus which records and registers in an instant, with great accuracy, the votes of legislative bodies, thus avoiding loss of valuable time consumed in counting and registering the votes and names, as done in regular manner; …"

When I first read about the story of Edison's Vote Recorder a number of years ago, I recall thinking to myself, “OK, this sounds like a great idea.” That had to have been a huge improvement! Of course! It's so efficient; who wouldn't want this! However, here is an account of the feedback received upon showing the Vote Recorder invention to a Congressional committee chairman:

"If there is any invention on earth that we don't want down here, that is it. Filibustering and delay in the tabulation of the votes are often the only means we have for deferring bad or improper legislation." (Source: Rutgers University, Edison Papers)

At this point, Edison claimed he would never again invent something that wouldn't sell, and he focused his efforts on creating things that people wanted, needed, and were willing to buy. This is an incredible insight that many organizations and innovators should truly take to heart.

Ugh! Still so much failure!

Christensen and Raynor in The Innovator's Solution (HBS Press, 2003) underscore the prevalence of this issue today: "… despite the best offers of remarkably talented people, most attempts to create successful new products fail. Over 60 percent of all new-product development efforts are scuttled before they ever reach the market. Of the 40 percent that do see the light of day, 40 percent fail to become profitable and are removed from the market. By the time you add it all up, three-quarters of the money spent on product development investments results in products that do not succeed commercially." This is amazing! Three-quarters of the money spent on product development produces stuff that people don't want or need!

While an argument can certainly be made that some of the stuff people create is simply "before its time," (note: the vote recorder was about 100 years before its time), and there is a role for this type of effort; that is A VERY LONG time to wait in order to realize a return on that investment. It can also be argued that through the process of creating the widget that nobody wants or needs right now, one might "learn" something that can be leveraged in subsequent innovation efforts. Unfortunately, given the current failure rate cited by Christensen and Raynor, I'm afraid that there probably isn't a lot of learning happening either (or at least not being retained). Edison, in addition to being a brilliant innovator, was also arguably one of the best at accepting and learning from failures. When asked by a reporter about his many failed efforts to invent the carbon filament for the electric light, Edison replied, "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work." The problem for most of us operating in today's world, is that we simply cannot afford chasing 10,000 cool ideas!

Solve consumer needs!

With innovation failure rates in the 75 percent range, Christensen and Raynor lay out their approach for solving the high failure rates of innovators, in essence, improving your odds as an innovator. Their approach is "based on the notion that customers 'hire' products to do specific 'jobs.' The classic reference for this notion comes from Harvard professor, Theodore Levitt : "People don't want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!" In other words, people don't need a drill, they need a hole; and the drill is the solution for their need.

Tony Ulwick in "What Customers Want" (McGraw Hill, 2005) takes this notion even further and states that, "To figure out what customers want and to successfully innovate, companies must think about customer requirements very differently. Companies must be able to know, well in advance, what criteria customers are going to use to judge a products value and dutifully design a product that ensures those criteria are met. These criteria must be predictive of success and not lagging indicators."

The criteria for gauging the likelihood of future success that Ulwick details surround the notion of understanding desired outcomes. For our above example, the individual's desired outcome is a quarter-inch hole. In essence, you need to understand how important it is for consumers to produce quarter-inch holes and the extent to which consumers are satisfied with their ability to create quarter-inch holes when they want to produce them. The higher the level of importance and the lower the level of satisfaction, the greater the opportunity for new product innovation.

Keep digging deeper!

Or just ask… Why? Why? Why? Why? Why?

Let's continue to build just a bit more upon our above desired outcome of having a quarter-inch hole. For me - being the naturally curious person that I am - I wonder why the person needs the quarter-inch hole in the first place. What do they actually need the hole for? It seems to me the hole is a solution for yet another desired outcome - perhaps to run a wire from one place to another, in order to connect a thermostat in one part of a home to the furnace located in another part. As we continue to push by asking 'why' a few more times, we have the opportunity to learn that maybe the desired outcome is the ability to regulate a home's temperature from a location that is up stairs from the furnace. But as we ask why some more, we learn that the ultimate desired outcome is to stay comfortable in their home. If we ask why yet again, maybe we get an answer like, "so I don't freeze to death." Rule of thumb - as soon as the answer to your 'why' question results in death, use the outcome from the prior answer. But, now we've discovered a desired outcome, or need, that is very real, very large and will always exist! People are always going to want to stay comfortable in their homes. We can come up with lots of ways to address this need!

Solving customer problems was actually the magic behind Edison's genius. He set out to solve large-platform, persistent needs. When you do this, you have the ability to innovate something that consumers want, need, and are willing to buy. The electric light in fact solved one of these large-platform needs. Prior to electricity and the electric light, people used candles and gas / oil lamps to see in the dark. The old solution for being able to see in the dark was fire. This sometimes unfortunately resulted in someone's home or place of work catching on fire and burning down. The electric light was created because of Edison's knowledge of electricity, his curious nature and his drive to create something that solved a larger-platform need - that being, see more safely in the dark.

So, as I safely sit here in a room lit by a couple lamps working on a computer that is powered by electricity, I have to give thanks to one of America's true pioneering innovators - Thomas Alva Edison - on his 165th birthday. Thank you for the light and the insight! - Woody Bendle